|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2016 Season | Edition No. 20 | July 18, 2016 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

LET THE SECOND HALF BEGIN! Brethren:

With the 2015 All Star Game now in the rear-view mirror, it is time for the second half of the Hot Stove League campaign to unfold. Some of the prevailing questions: Will the Wahoos and Cubs continue their neck-and-neck battle for supremacy in a two-team race, thumbing their collective noses at the rest of the HSL brotherhood? Will Possum’s acquisition of Steven Strasburg be the silver bullet to the supersized heart of Brother Shamu? Or will the frail fireballer from San Diego once again break down from the rigors of pitching in the District of Columbia and validate Skipper’s swap of Strasburg for LeMahieu and Santana, and aid the Senators in avoiding yet another finish in the league bowels? Will the Tigers be able to maintain their late first half momentum and begin to narrow the gap between 3rd place and the top two? Will any of the Killer B’s (Bums, Bombers and Blues) be able to shake off the mantle of mediocrity and make a move upward in the standings; or will they, with slumped shoulders, watch despairingly as they drop down in the standings, past even (egad) the saggy Skipjacks?

These, and other questions, will be answered in the fullness of time. Strap yourselves in, fellas, and enjoy the second half ride.

ALL-STAR REDUX: THIS BUD’S FOR YOU, BUD

I don’t know how many of you watched the All-Star Game last Tuesday night, but for my money, it was one of the best that I have seen, for at least seven reasons:

My feelings for former MLB Commissioner Allen Huber “Bud” Selig are even less fond than those for Big Papi, but I think it is only fair to give credit where credit is due, regardless of the identity of the Creditee. Although it was born out of embarrassment and seeming desperation, Selig’s pronouncement in 2003 that the winner of the MLB All-Star Game would be awarded the home field advantage for that year’s World Series has turned out to be a praiseworthy and farsighted decision. As it turns out, even wealthy and spoiled Major League ballplayers really do want to win the World Series, and they understand that having the home field advantage can go a long ways toward achieving that (8 out of the last 10 World Series champions had the home field advantage). In short, Selig’s decision has made the All-Star Game competitive and real, and it remains--by a tall margin--the best and most enjoyable all-star contest in major league sports. You may disagree if you like, but the NBA All-Star game is a complete joke, featuring a whole bunch of overpaid, overtatted punks trying to outscore each other without playing a lick of defense; the NFL Pro Bowl is so lame that I can’t even do it justice in describing it, because I have never actually watched it; and, frankly, I don’t even know if the National Hockey League hosts a similar contest, but if it does, I’ll bet it sucks.

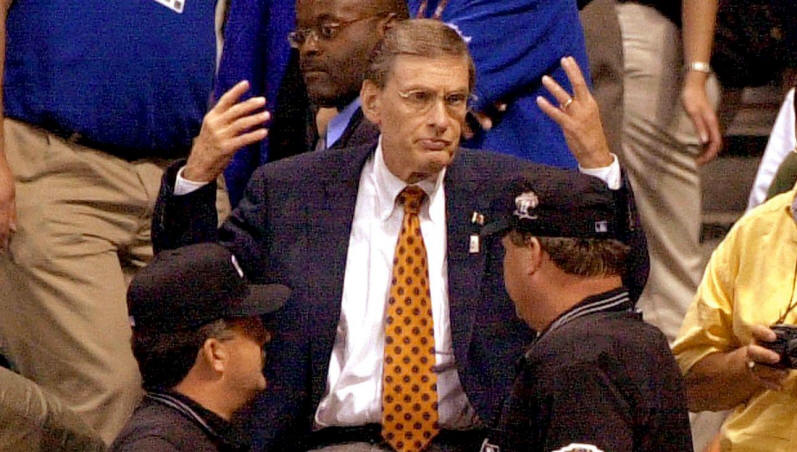

So even though I can still see Bud, in my mind’s eye, looking like the most uncomfortable undertaker of all time as he fidgeted and fretted before declaring the 2002 All-Star Game “a tie,”

and even though it was only because of his humiliation and embarrassment in making this call that later led to his decision to award home field advantage to the All-Star Game victor, I still say, “Here’s to you, Bud,” for giving us the best All-Star game in the business.

HEY, SMART GUY, WHAT ABOUT THIS?

Between the thirteen of us, we all think that we are pretty savvy and knowledgeable baseball men, and so with each of us drafting 30 players on Draft Day, for a total of 390, you would think that we would have been able to snag virtually all of the best players in the game. However, as you may have noted, there were quite a number of All-Stars who were not even drafted in our HSL Draft this year, as follows:

Eduardo Núñez Steven Wright Brad Brach Will Harris Aaron Sanchez Aledmys Díaz Bartolo Colón

Moreover, there were a number of players who made the All-Star team who were drafted quite late in the HSL Draft. Congrats to the clever managers who practiced such admirable forbearance before picking up these players so late:

It is also noteworthy that two of the first round draftees this year, Andrew McCutcheon of the Senators, and Carlos Correa of the Redbirds, both have stunk it up so bad during the first half that they didn’t even make the All-Star team. Thanks, Cutch.

SALUTE TO SCREECH

A hearty “Hey, thanks!” and a crisp Five-Star General salute to our own Brother Screech for authoring another exemplary and edifying edition of Butterfly Blessings last week. Oh, sure, I know that the official title of his rag is The Monarch Missive, but who the hell really understands what that is supposed to mean? In any event, however Screech wants to title his guest feature, that is his business, but it deserves a shout-out nevertheless.

While I heartily enjoyed Screech’s ranking of the use and non-use of HSL league nicknames, I must take umbrage at his dubbing of yours truly as “Old Onion Skin.” I mean, what gives, dude? Are you calling me fat, too? Are you saying that my teeth are coffee-stained, and my nose hairs need some work? That I have missed a typo here or there while trying to entertain you clowns? Thin-skinned? I have no idea what you are talking about. So shut up.

And not that I take any delight whatsoever in pointing out oversights, Screech, but you have omitted several oft-used nicknames for the Hot Stove League boys, including, but not limited to, the following:

Bender, Foster and Big Johnny for Itchie; Magpie for Mitch; McJester for Stretch; Whitesot for Big Guy; The Teutonic Tickler for BT; Beelzebub, Devil Boy, and Lucifer for Possum; Fred Garvin, Male Prostitute, for Mouse; The Silent Assassin for Dennis; Snickler and The Red Badge of Courage for Shamu; MasterSpieler and U-Bob for Underbelly; Bridesmaid Revisited and Jim Ed for Tirebiter; Skeezix’s Soulmate for you; and last, but not least, Old Leather Skin for yours truly.

But don’t feel bad, because after all, you are the league neophyte. Not to be confused with neofascist. Or Neoprene.

Thanks again. Well done, brutha.

BEANTOWN BOONDOGGLE

As this issue of From the Bullpen makes its way through cyberspace to your feasting eyes, I will be several days into a glorious work-and-play junket to Boston and other parts east, with planned visits to Edward A. LeLacheur Park in Lowell, Massachusetts, to see the Spinners, and to Northeast Delta Dental Stadium in Manchester, New Hampshire, to root on the FisherCats. While we are in the Hub, a visit to Fenway may also eventuate, as well as the sampling of some of the fine Italian cuisine of North Boston. One if by land, two if by sea, there’s a plate of linguini just waiting for me!

More later on Beantown Revisited.

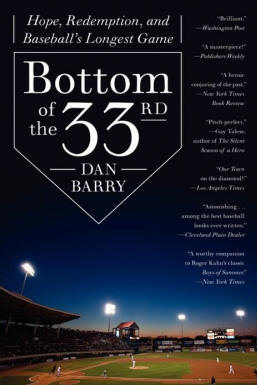

BOOK REPORT: Bottom of the 33rd

As I mentioned last issue, I have been reading and just recently finished a marvelous baseball book entitled Bottom of the 33rd, written by a non-baseball writer by the name of Dan Barry (he has a column with the New York Times) and published by Harper in 2011. Although I picked up this book in an airport book store in January on a lark--having visited McCoy Stadium in Pawtucket a couple of years ago on a deposition trip, where I read a bit about the historic 33-inning game at a display at the park--I will go out on a limb and say that this is one of the best baseball books I have ever read. And since 90% of the books that I read are baseball books, I guess that also means it is one of the best books of any kind that I have read.

Since I had never before known of the author, nor had I heard any advance billing about the book, nor received any recommendations, I assumed that Bottom of the 33rd would be a rather lackluster and work-like recounting of the subject game, inning by inning, batter by batter; and perhaps because of this, the book sat on my nightstand for almost six months before I began reading it. However, as soon as I began my journey into the book, I recognized almost immediately that it was nothing like I had envisioned. It is a vigorously-researched, spell-bindingly told story of the building of McCoy Stadium (named after former Pawtucket mayor, Thomas P. McCoy), the rescuing of the moribund Pawtucket franchise by then-owner Ben Mondor, and the lives of the players who participated in the marathon, record-setting game--from future Hall of Famers Cal Ripken, Jr. and Wade Boggs, to journeyman minor leaguer Dave Koza from Torrington, Wyoming, who would never make it to the Majors because of the Red Sox’ glut of talented first basemen.

The book is really a tapestry of vignettes about a host of different baseball men, linked by common cause, including:

Cal Ripken, Jr.--the Rochester third baseman who was raised following his father throughout professional baseball, and who would go on to replace Lou Gehrig as the game’s all-time Iron Man, playing in 2,632 consecutive games.

Bobby Bonner--the Rochester shortstop, a Bible-brandishing young Southerner who would be called up to the Majors and be charged with an error on a critical play, resulting in a confidence-shattering berating by the vesuvian Earl Weaver, and reportedly leading to the monumental decision to move Ripken from third base to short.

Wade Boggs--the chicken-eating, superstitions-obsessed native of Omaha who was still not a sure bet to make it to the Majors, and in fact was left unprotected by the Red Sox organization when it announced its 40-man roster that year, but who was claimed by no other teams.

Bruce Hurst--the goofy, immature Mormon from St. George, Utah, who refused to succumb to his teammates’ encouragement toward wine, women and song, but who had so little confidence in his pitching ability that he flat out quit the Pawtucket team more than once and had to be cajoled back into the fold.

Bobby Ojeda--the lefty hurler, son of a California plumber, who would later be traded to the Mets and subsequently face several of his former Pawtucket teammates in the 1996 World Series, which of course was won by the Mets after Billy Buckner let Mookie Wilson’s ground ball go through his wickets in Game Six, following which, after the final contest, Bruce Hurst and Rich Gedman made their way through the victorious Mets’ clubhouse to congratulate their former teammate Ojeda, in a great show of sportsmanship and Minor League brotherhood.

Dave Koza--the pride of Torrington, Wyoming, a four-sport star athlete (football, basketball, baseball and track--who once won 1st place in the discus, long jump and triple jump in a meet), the baseball-loving Koza attended Eastern Oklahoma State College (the Mountaineers) and signed a contract with Red Sox scout Danny Doyle and then started his minor league baseball career in Elmira, New York, then to Winter Haven, then to Bristol, Connecticut, and then to Pawtucket, where it would terminate.

Sam Bowen--described in the book as a “baby-faced country boy from the coastal marshes of south Georgia,” he played college ball at Brunswick Community College in North Carolina and then at Valdosta State College in Georgia before being drafted by the Boston Red Sox in 1974. He quickly worked his way up the organizational ladder to become a star in Pawtucket and a Boston prospect, but after being traded to the Tigers, he queered the deal by telling the Detroit GM that he had a pulled hamstring in his right leg. The deal with Detroit was off, and Bowen became persona non grata in the Red Sox organization, getting only 22 at-bats in the big leagues and recording 3 hits, 1 HR, and 1 RBI. Years later, he would describe himself as another Crash Davis, a home-run heartbreak of the Minor Leagues.

Russ Laribee--the designated hitter for the Pawtucket team, Big Russ struck out 7 times in this extra-inning contest, more than a Double Hat Trick.

Since I am a realist (about some things) and I realize that the vast majority of you will not ever read this book, I want to at least share with you my favorite part of the book, a several-page vignette about Joe Morgan (not the former Reds player turned TV broadcaster, but the other baseball Joe Morgan), who has spent a richly-filled lifetime as player and manager in the minor and major leagues, but mostly in the minor leagues. It was this Joe Morgan who was tapped to be the interim manager for the Boston Red Sox in 1988 when John McNamara was fired, but whose team then did so well he essentially forced the ownership and management to make him a full-time skipper, a post that he held for parts of three seasons, until he was replaced by Butch Hobson.

Anyway, here’s the story of Joe Morgan, baseball lifer:

Nearly thirty years later, on another inclement spring day in New England, Joe Morgan will nestle into a comfortable chair in his living room in Walpole, Massachusetts, his hometown. His feet will be shod in blue slippers, each one crowned with a red capital B—for Boston Red Sox. His wife, Dottie, will busy herself in the kitchen. On a wall there will hang a sign that reads: “A baseball fan lives here . . . with the woman he never struck out with.” It will be a nice scene, a tranquil scene, until Morgan recalls that distant play.

“He ran toward first and the ball jumped up and hit him in the foot!” the white-haired man, nearly eighty, will say. And the 22nd inning of this long-ago ball game in Pawtucket will unfold again in his living room. “He’s out!”

Joe Morgan’s baseball passion never cools. The son of immigrants from County Clare, he starred in baseball and hockey at Boston College, where he learned how to apply a Jesuitical rigor to the rules and nuances of the game, and continued his studies during summers by playing for the Hopedale mill town team in the Blackstone Valley League for $30 a week. He’d spend the day working—in a mill one year, at an inn two other years—then play baseball at night against mill workers, college students, and crusty baseball professionals, including a few former major-league pitchers who knew how to snap off a 12-to-6 curve (“I found out how good I wasn’t in a hurry,” he will say). Once he earned his bachelor’s degree in American history and government, he set it aside to embark upon a long career as an itinerant baseball man, his every port of call remaining so vivid in his mind that he will summon them in a laconic Yankee recitation, like a salty Robert Frost asked once again to deliver “The Road Not Taken.” “Well, the first team I played for was the Hartford Chiefs in the Eastern League. Next year I was at Evansville, Indiana, in the Three-I League. Following two years I was in the U.S. Army as a ground pounder.” Ground pounder? “A guy that’s in the army is a ground pounder just by walking around.” Where was he? Oh, yes. The Hartford Chiefs, in 1952. The Evansville Braves. Then down to the Jacksonville Braves in the Sally League. The Atlanta Crackers in the Southern League. The Wichita Braves in the American Association. The Louisville Colonels. The Charleston Marlins. Back to the Atlanta Crackers, now in the International League, for a couple of years. Then back to Jacksonville, but this time for a team called the Suns. Then, at the age of thirty-five, down to the Raleigh Pirates, in the Carolina League, in 1966. Sprinkled among those thirteen years in the baseball wilderness were bits of four seasons in the major leagues, with the Milwaukee Braves, the Kansas City Athletics, the Philadelphia Phillies, the Cleveland Indians, and the St. Louis Cardinals. He was more than a cup-of-coffee guy, but not much more: two cups and maybe a doughnut, to go with a .193 batting average and an ever-expanding repository of baseball knowledge and lore. He will describe the heat-baked infield at the ballpark in Keokuk, Iowa, as the worst he ever played on; explain why Jimmie Foxx was the best all-around ballplayer in history; remember the name of a long-forgotten minor-league pitcher, Al Meau, who hit a ball through a tire hung in right field in Bluefield, West Virginia, winning enough money to pay his rent for the 1947 season; vividly describe a strange dinner that he and Dot shared with Ted Williams and his girlfriend; and discuss, with professional authority, the many ballpark stunts he witnessed over the years, including this: Joe Engel, the gimmick-loving owner of the Chattanooga Lookouts and acknowledged “Barnum of Baseball,” would cover the infield with hundreds of dollar bills, along with a fin and a sawbuck here and there. The players from both teams would be positioned along the first- and third-base lines, while a lucky fan standing at home plate would be told that he had thirty seconds to pocket as much of the money as he could, after which the players would dive in. But it would never get to thirty seconds. Shortly into the countdown, one of the ballplayers would feign a move, tricking the other ballplayers into crossing the line, and a monetary free-for-all would ensue. “I found out the best way to do it was to run out there and fall on the ground, and cover as many as you could, reach around the side, scoop up and then get ’em underneath you,” Morgan will recall. “I think I got seventeen bucks one time.” After his playing career ended, Morgan continued his baseball peregrinations as a manager: Raleigh, North Carolina; York, Pennsylvania; Columbus, Ohio; Charleston, West Virginia; a year as a coach with the Pittsburgh Pirates; and then back to Charleston. Meanwhile, he and Dottie were raising a family and paying a mortgage in their native Walpole, so he took any job he could find in the off-season—so many, in fact, that he once compiled a list of them and filed it in a small wooden box, along with other idiosyncratic information: every horse to win at least fifty races; the countries that produced the most baseball players, besides the United States and Canada (“Ireland had a shitload of them in the early going”); prominent players who played just one year with the Boston Red Sox (Jack Chesbro, Juan Marichal, Orlando Cepeda, Tom Seaver . . .). “I was a substitute schoolteacher. I was a bill collector. I took the census in this town. I was an oil man. A coal man. Construction worker. I worked for Polaroid. Raytheon. American Girl Shoe. I worked for Uncle Sam for two years in the U.S. Army; can’t forget that. I went to winter ball, four years. I coached the Boston neighborhood hockey team. Oh, yeah, I worked for the post office for a couple of years.” In early 1974, the team in Pawtucket, just twenty-five miles south of Walpole, had an opening for a manager. Sensing another faint chance to manage in the major leagues someday, Morgan expressed his interest to the midlevel executives in the Boston organization. When nothing came of his inquiries, he boldly called Dick O’Connell, the Red Sox general manager, at home. O’Connell’s initial response: How the fuck did you get my telephone number? Morgan’s initial thought, rendered in Morgan-speak: Holy Christ, that’s negatory. But Morgan plowed on, saying he was the man for the job in Pawtucket. O’Connell floored him by responding: There’s a ton of people who want this job, but nobody’s asked me about it, and I’m the boss around here. You got the job! So began New England’s gradual embrace of its prodigal son, a baseball savant whose managerial decisions were rooted not in statistical analysis but in what he had learned from the Jesuits and those Blackstone Valley veterans, and from all that time spent in places large and small, in Milwaukee and Keokuk, playing beside the great and the forgotten, for teams called the Cardinals and the Crackers. He won over most of his players with his paternal bluntness and his ability to say I’ve been there; I’ve been cut, demoted, uncertain of my future; I’ve been in your cleats. He charmed fans with his on-field histrionics and odd linguistic style, a kind of Walpole meets Canterbury, in which his nonsensical catchall phrase, “Six, two and even,” seemed to add up somehow. And he earned the respect of umpires for his deep knowledge of the rules of baseball, although they found his goading, exhibitionistic manner less than endearing. After being ejected one time in Columbus, Morgan did not leave until a sheriff arrived to escort him from the field, after which the unamused sheriff declined his invitation to share a clubhouse beer. For all his antics, Morgan possessed the maturity that comes from hard-earned perspective. He understood the essential truth of baseball: that to be paid to throw and bat a ball around is a blessing. Real work came after the last game of the season, when he returned to the ranks of the stiffs, doing whatever he could to provide for his family. Soon after landing the manager’s job at the Pawtucket Red Sox, he began working the off-season with the Massachusetts Turnpike Authority, mowing the last of the grass, picking up garbage, plowing snow. He’d clean up around the toll plazas, and when he found an errant coin, he’d pocket it. Joe Morgan and Pawtucket, then, were a perfect fit: modest, time-tested, underestimated. He and the owner, Ben Mondor, understood and respected each other. After every road trip, for example, Morgan would return to McCoy to find a fifth of Chivas waiting for him, courtesy of Mondor—except for the time the team lost nine of ten on the road. Left on his desk was a miniature bottle of scotch: an airplane nip. He laughed his ass off. One night, Ben and Madeleine Mondor treated Joe and Dottie Morgan to dinner at the Lafayette House, an upscale colonial remnant on Route 1 in Foxboro, not far from Walpole. After a couple of drinks, Mondor got down to business, saying to Morgan: If you promise to be my manager for the rest of your baseball career, your family will never have to worry about another dime again. College. Money. You won’t have to worry. After a pause, Morgan gently gave his answer: I can’t, Ben. Why not? Indeed: why not? After thirty years of wandering the country in pursuit of a game, Morgan was being offered a dream of an opportunity by a multimillionaire friend whose word was gold. Stop your traveling. Stay in minor-league baseball. Commit to Pawtucket. All will be well. It sounded so inviting. Why not? Because Morgan, not yet fifty, was still, at his core, a professional baseball player, and professional baseball players are conditioned to take one step, one base, and then the next base, and the next, and not stop until they have made it home. And home means only one thing. I can’t, Ben. Why not? Because someday I want to manage in the big leagues.

Deep in his comfortable chair, his box of lists by his side, Morgan will smile at the memory of his long career as the manager of the Pawtucket Red Sox: nine years, from 1974 to 1982. The good teams. The lousy teams. The bottles of Chivas. The characters. Win Remmerswaal, for example, that crazy Dutchman, imploring Morgan not to put him into a game until the 8th or 9th inning because he was still adjusting to the time zone. For a moment the man in Red Sox slippers will disappear into that distant place, where his office was a glorified closet, and the clubhouse showers scalded his skin, and the stadium was so empty and cold some nights that it felt like a morgue—and he will want to go back. “Those were good times,” he will say.

Joe Morgan. A character’s character. And when I last checked, he is still alive, at 85. Man, would I ever love to treat him to a burger and a beer down at Dinker’s, and to simply sit back and listen to him talk about his peripatetic life in baseball.

END OF STORY

Since most of you won’t read Bottom of the 33rd, I won’t worry about spoiling the ending by telling you here what happened. After the longest game was finally suspended after 32 innings when the Pawtucket owner eventually was able to get hold of the International League president, the game was scheduled to be concluded on June 23, 1981, as part of a doubleheader. Because Major League Baseball was currently on strike, there was an enormous amount of attention paid to the resumption and completion of the game, including attending journalists from Japan and other unlikely places.

Taking the mound for the PawSox for the top of the 33rd inning was Bobby Ojeda. Toeing the rubber for the Red Wings was future Detroit Tiger hurler Steve Grilli, father of current Blue Jays reliever Jason Grilli. In the top of the inning, Ojeda worked around a walk and retired the side without yielding a run. In the bottom of the 33rd, the suspense of the game’s outcome quickly came to an end when the first three Pawtucket hitters reached base without a single out, and Speck came in to relieve Grilli with the bases loaded. Up stepped to the plate big Dave Koza from Torrington, Wyoming, determined to make the bosses upstairs in the Red Sox organization take notice. On a 2-and-2 count, Koza attacked a Speck curve ball and sent a flare over the left side of the infield and just short of the outfield to drive in the winning run, and the PawSox were the winners of the longest professional baseball game by a score of 3-2.

“Koza reaches out and, almost apologetically, connects.” Unfortunately, Koza’s heroics weren’t enough to get him called up by the Red Sox that September of 1981--or in any subsequent September--but there will always be an exhibit at the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown with his picture and the inscription that he was the hitter that ended the longest game.

In conclusion, Bottom of the 33rd is a must read for any serious baseball fan. On a scale of 1 to 10, I give it a score of 10 on the Skipper book meter.

LIVING ON TULSA TIME

The week before last, I made the drive down to Tulsa to meet with an expert witness that I am using in a case, Phil Barton, a native Okie who was raised in Eufaula, Oklahoma, and who is now the director of the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit at the Children’s Hospital in Tulsa. Although I am not sure if this was on the level or not, Dr. Barton claims to have been baby-sat by the Selmon brothers [Lucious II (1951), Dewey Lewis (1953), and Lee Roy (1954)] when he was very young, apparently through some connection with his father serving as the president of the OU Quarterbacks Club. Since the case he is reviewing for me involves meningitis, the good doctor thought I would find it interesting that the Selmon boys’ father had meningitis as a youth, and that it left him with lifelong neurological deficits and a fully mature size of only about 5-foot-7 inches tall and maybe 160 pounds.

The air service between Omaha and Tulsa is spotty at best and requires a connecting flight through somewhere else, so I decided that driving instead of flying was the way to go. It is a straight shot on Highway 75 all the way from South Omaha to Tulsa, a span of about 380 miles. Although I have made the drive on south 75 into Topeka on countless occasions (my mom was raised in Topeka, and my Uncle Dean still lives there), I had never before (if memory serves) made the drive from Topeka to Tulsa. While it is a pleasant and easy enough drive, there is little else to recommend it, other than as a cheap corridor of access to Tulsa.

I think I have been to Tulsa once before, for a deposition many years ago, but I could be thinking of Oklahoma City, where I have been several different times for depositions. In any event, I was thoroughly impressed with the downtown Tulsa area, which is clean and modern and seemingly safe. Although I guess I could look it up, it appears that most of their major downtown skyscrapers were built in the art deco style of the 1920s and ’30s and are still remarkable and beautiful structures. In recent times, they have added some beautiful and architecturally innovative new buildings, including the BOK Center, shown below.

Thanks to my good fortune of having the top travel agent in the state on staff (Linda), I stayed in the beautiful and historic Mayo Hotel, a Tulsa landmark and oasis for visiting oilmen since opening its doors in 1925. When it first welcomed paying customers, the Mayo was the tallest building in Oklahoma and the only place in the state with cold tap water and rooms with ceiling fans, important accoutrements during the blazing Tulsa summers. Recently renovated and modernized, it is one of the nicest hotels that I have stayed in anywhere, right up there with the Baltimore Days Inn*.

ONEOK FIELD

Although my meeting with Dr. Barton was invaluable, and my stay at the sumptuous Mayo Hotel rejuvenating and pleasurable in the extreme, the centerpiece of my Tulsa trip was, of course, a visit to another minor league baseball stadium. Knowing that this trip was on the horizon for several months, I have been waiting with childlike anticipation for my visit to ONEOK Field, a jewel of a structure that first opened to the good denizens of Tulsa in the late spring of 2010.

ONEOK Field, Tulsa

After plunking down a fin for a general admission ticket, I made my way into ONEOK Field to witness a game between the Tulsa Drillers, a Double A affiliate of the Los Angeles Dodgers, and the San Antonio Missions, the Padres’ Double A farm club. Arriving almost an hour before game time, I was able to walk the concourse and check out all aspects of ONEOK Field, from every perspective. As with many of the modern open concourse ballparks, the sightlines are terrific, and with seating for 7833 fans, there truly isn’t a bad seat in the house. I should know, because with only a few hundred people in attendance, I was able to try out almost all of them.

Although the temperature was a roasty 98 degrees when I got to the park, with ample humidity, I was able to purchase a 33 degree Dos Equis for a reasonable sum of $5.50, and the chilled ale both lowered my temperature and lifted my spirits. So did the three (maybe) or four (more likely) similarly frosty Dos Equis delights that followed. By that time, I was convinced that I am the most interesting man in the world, in part because I can now add Tulsa to my baseball résumé and speak from experience about all that commends it.

People from Tulsa are real nice, too. They speak with a slight southern drawl, less pronounced than the dialects of some of their, shall we say, sometimes-too-pleased-with-themselves neighbors to the south, just across the Red River. Tulsans are unpretentious, tough (I saw lots and lots of people out walking and even running in the 100+ degree heat earlier in the day), and just folksy enough, but not overly so.

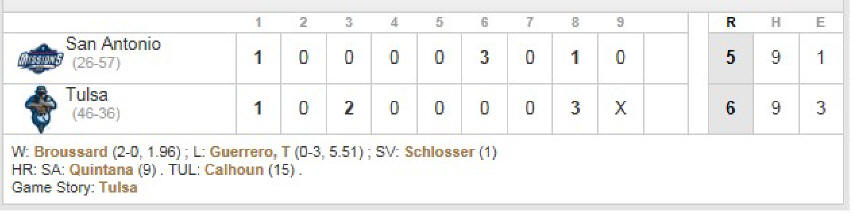

I saw a whale of a game on the field, with the Drillers taking the early lead by the score of 3-1, the Missions going out in front in the top of the 6th on a 3-run blast from Gabriel Quintana, and the Drillers reclaiming the lead in the bottom of the 8th and then holding on to win by the score of 6-5.

The crowd was treated to back-to-back miscues by the slugging Missions center fielder, uniquely named Franchy Cordero, who had opportunities to make stellar plays on hard-hit balls to the warning track on consecutive Drillers at-bats, only to do his best Lonnie Smith** imitation and misplay each ball into an extra base hit.

But for me the story within the story was all about the Drillers’ left fielder, Lars Anderson, a tall (6-foot-4), strapping (215 pounds--exactly the same as my current weight, but perhaps distributed a bit more attractively), 28-year-old from Fair Oaks, California, who immediately looked out of place to me when I saw him stretching during the pre-game warmups. When I looked him up in the program and saw his date of birth, I immediately wondered what he was doing in Double A ball at his age. I figured that he was either on a rehab assignment or on his way back down the professional baseball ladder, hanging on for dear life for another shot at the Bigs.

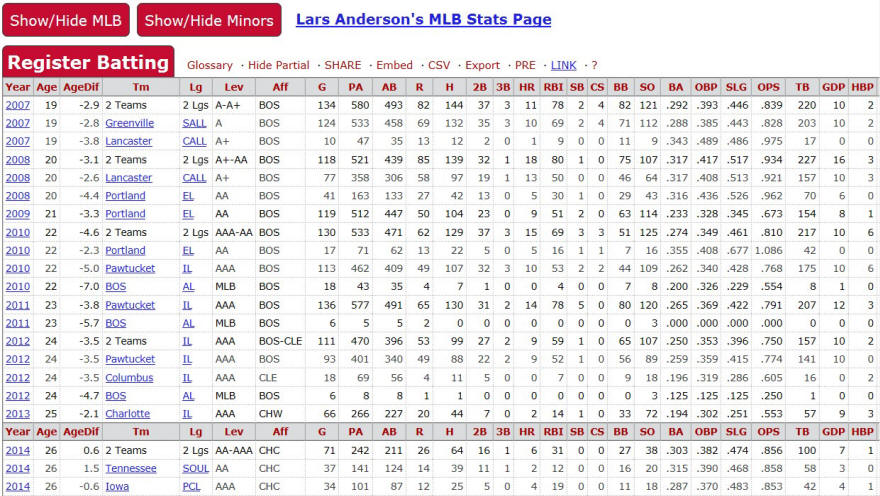

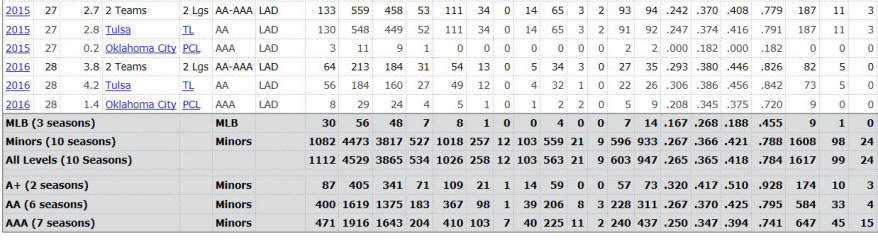

Having recently read and reported on Out of My League and Bottom of the 33rd (both of which deal extensively with the trials and tribulations of career minor leaguers trying to make it to The Show, and stay there, in spite of talent deficits, injuries, bad timing, and bad luck), I was thoroughly intrigued with the baseball journey of Lars Anderson. In researching Lars Anderson’s professional baseball history on my iPad, I learned that he is one of those extremely talented baseball players who has been good enough to make it through every level of the minor leagues and all the way up to the Bigs; but unfortunately, just not good enough to stick. His minor and major league numbers, detailed below, tell the story of Lars Anderson.

In spite of his low likelihood of making it back up to the Major Leagues in a talent-laden organization like the Los Angeles Dodgers, it was still a pleasure to watch Lars Anderson play. Unlike most of his teammates, he knew exactly how to foul off pitches that he knew he couldn’t handle, using his deft bat work to extend at least two or three of his at-bats, masterfully. That, and he carried himself with an utter bearing of confidence and professionalism at the plate, looking every bit like someone who has seen it all and done it all before, and at a higher level.

For the evening, Lars’ line score was as above, and he acquitted himself well in the field as well. He single-handedly put a dagger into a Missions rally by hustling in to scoop up a single and then fire a dart to the plate to nail the runner who was trying to score from second. Here’s a picture that I took of him as he came into the dugout after uncorking this splendid throw.

Maybe Lars has no pretensions about making it back up to the Major Leagues and having more than another cup of coffee. Maybe moments of glory after making throws like this one are enough to keep him around, even at the Double A level. Let’s wait and see.

I include the below pictures of the Drillers’ mascot, Hornsby the bull, just for McJester:

ONEOK Field was the 44th minor league ballpark I have now visited, and I have been waiting for a suitable sample size before I start ranking them in order of preference. I think that will be my off-season project for next winter. For now, with the memories of ONEOK Field fresh in my mind, I will say that it probably deserves a spot in the Top Ten of the minor league venues I have seen so far. Stay tuned.

NEXT WEEK: THE 7TH INNING STRETCH

Looking forward to it, McJester. Please don’t disappoint!

Skipper

P.S. Oh, yeah, following the principle of “to each his own,” I decided to go ahead and “waste a ton of FTB space with a lengthy recitation of the current standings and individual player point totals and leaders, who’s hot, etc.,” and have posted same below.

STANDINGS THROUGH WEEK 15

WEEKLY POINT TOTALS

TOP 25 PITCHERS

WHO’S HOT -- PITCHERS

WHO’S NOT -- PITCHERS

TOP 25 HITTERS

WHO’S HOT -- HITTERS

WHO’S NOT -- HITTERS

* * * * * * * *

*Okay, just kidding on that one. But I do have fond memories of the Baltimore Days Inn since it put up the HSL boys for our league visit to Camden Yard, as well as Scott and me and the girls for our trip there to pay tribute to Cal Ripken in January 1996 where our stay was extended because of the east coast blizzard that blanketed Baltimore. Although it became less and less humorous as the days wore on and the food supply dwindled, the byline for that latter hotel stay was, “Nothing’s too good for our girls!” In retrospect, that calamitous visit may have been the beginning of the end of my first marriage.

** As Bill James once famously wrote of Smith: “I will say, though, that the real cost of Lonnie's defense is not nearly as great as the psychic impact of it. He makes you wail and gnash your teeth a lot, but he really doesn't cost you all that many runs. One reason is that he recovers so quickly after he makes a mistake. You have to understand that Lonnie makes defensive mistakes every game; he knows how to handle it. I mean, your average outfielder is inclined to panic when he falls down chasing a ball in the corner; he may just give up and sit there for a while, trying to figure it out. Lonnie has a pop-up slide perfected for the occasion. Another outfielder might have no idea where the ball was when it bounded of his glove; Lonnie can calculate with the instinctive astrophysics of a veteran tennis player where a ball will land when it skips off the heel of his glove, what the angle of glide will be when he tips it off the webbing, what the spin will be when the ball skids off the thumb of the mitt. Many players can kick the ball behind them without ever knowing it; Lonnie can judge by the pitch of the thud and the subtle pressure through his shoe in which direction and how far he has projected the sphere. He knows exactly what to do when a ball spins out of his hand and flies crazily into a void on the field, when it is appropriate to scamper after the ball and when he needs to back up the man who will have to recover it. He has experience in these matters; when he retires he will be hired to come to spring training and coach defensive recovery and cost containment. This is his specialty and he is good at it."

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||