| |

INDEX TO BOOK REPORTS

| |

Book |

Author |

Date of

Report |

Page |

|

|

Ol’ Pete |

Jack Kavanagh |

07/28/98 |

1 |

|

|

Memories of Summer |

Roger Kahn |

08/26/98 |

3 |

|

|

The Heart of the Order |

Tom Boswell |

09/09/98 |

5 |

|

|

Joe DiMaggio—The Hero’s Life |

Richard Ben Cramer |

01/31/01 |

7 |

|

|

When Pride Still Mattered |

David Maraniss |

05/15/01 |

11 |

|

|

George Washington |

Willard Sterne Randall |

11/14/01 |

13 |

|

|

Stranger to the Game |

Bob Gibson |

12/03/02 |

15 |

|

|

A Flame of Pure Fire |

Roger Kahn |

02/20/04 |

19 |

|

|

The Game |

Robert Benson |

02/19/04 |

21 |

|

|

Lords of the Realm |

John Helyar |

02/19/04 |

25 |

|

|

The Teammates |

David Halberstam |

08/31/04 |

29 |

|

|

The Curse of the Bambino |

Dan Shonnessy |

10/19/04 |

31 |

|

|

October Men |

Roger Kahn |

12/16/04 |

33 |

|

|

Catcher in the Rye |

John D. Salinger |

04/26/05 |

37 |

|

|

Don Quixote |

Miguel de Cervantes |

04/26/05 |

37 |

|

|

Luckiest Man |

Jonathan Eig |

05/10/05 |

39 |

|

|

Baseball in Omaha |

Devon Niebling/Thomas Hyde |

07/26/05 |

41 |

|

|

The Head Game |

Roger Kahn |

01/05/06 |

47 |

|

|

Foul Ball |

Jim Bouton |

02/13/06 |

49 |

|

|

The Summer Game |

Roger Angell |

02/13/06 |

49 |

|

|

Game of Shadows |

Mark Wada and Lance Williams |

04/12/06 |

51 |

|

|

Ball Four |

Jim Bouton |

07/18/06 |

53 |

|

|

The Summer Game |

Roger Angell |

07/18/06 |

55 |

|

|

1776 |

David McCullough |

09/13/06 |

59 |

|

|

The Old Ball Game |

Frank Deford |

09/13/07 |

61 |

|

|

The Era |

Roger Kahn |

12/21/07 |

63 |

|

|

The Tender Bar |

J.R. Moehringer |

01/03/08 |

69 |

|

|

How Life Imitates the World Series |

Tom Boswell |

04/17/08 |

71 |

|

|

The Echoing Green |

Joshua Prager |

04/25/08 |

75 |

|

|

Three Nights in August |

Buzz Bissinger |

06/18/08 |

77 |

|

|

Clemente |

David Maraniss |

07/17/08 |

79 |

|

|

Big Russ & Me |

Tim Russert |

10/01/08 |

85 |

|

|

The Bronx is Burning |

Jonathan Mahler |

11/14/08 |

87 |

|

|

The Heart of the Order |

Tom Boswell |

02/03/09 |

89 |

|

|

A False Spring |

Pat Jordan |

03/06/09 |

93 |

|

|

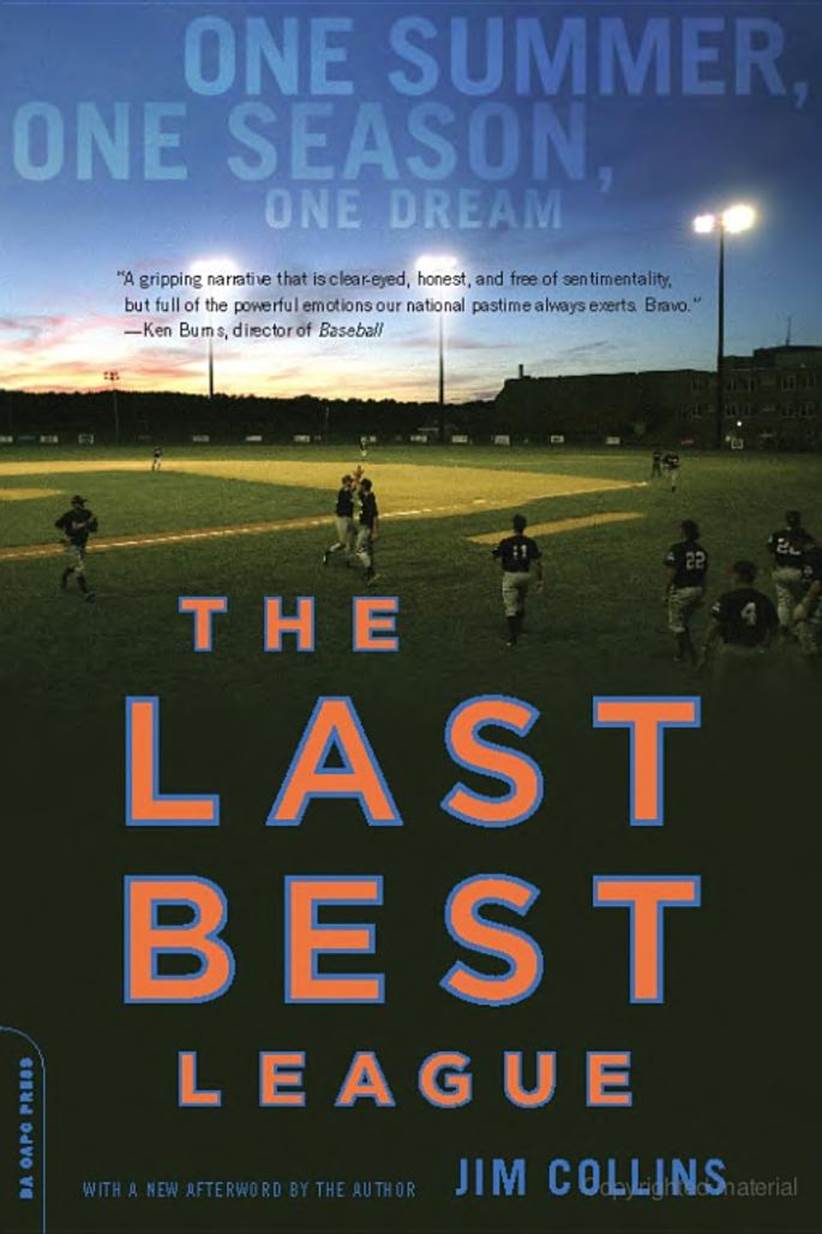

The Last Best League |

Jim Collins |

05/21/09 |

97 |

|

|

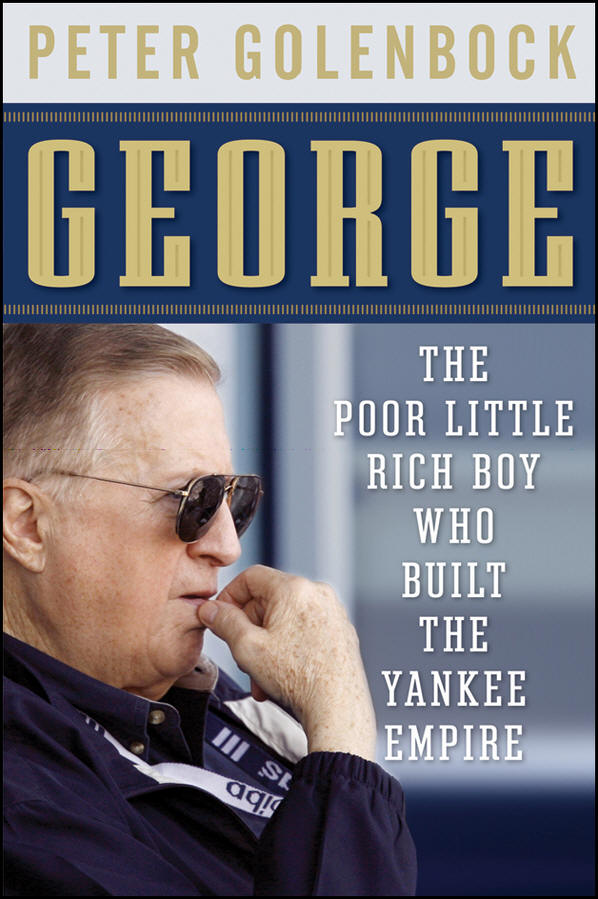

George |

Peter Golenbock |

08/10/09 |

99 |

|

|

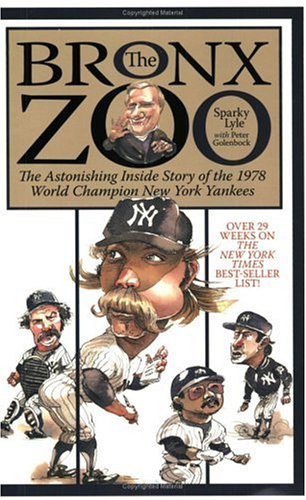

The Bronx Zoo |

Sparky Lyle with P. Golenbock |

10/28/09 |

103 |

|

|

The Machine |

Joe Posnanski |

12/04/09 |

107 |

|

|

Cracking the Show |

Tom Boswell |

12/23/09 |

111 |

|

|

The Snowball: Warren Buffett |

Alice Schroeder |

01/29/10 |

113 |

|

|

Chief Bender’s Burden |

Tom Swift |

03/04/10 |

115 |

|

|

9 Innings: The Anatomy of a Baseball

Game |

Daniel Okrent |

01/12/11 |

119 |

|

|

Last

Lion: The Fall and Rise of Ted Kennedy |

Peter Canellos |

02/09/11 |

121 |

|

|

The Yankee Years |

Joe Torre and Tom Verducci |

04/08/11 |

123 |

|

|

Counselor: A Life at the Edge of

History |

Ted Sorensen |

09/26/11 |

125 |

|

47. |

Five Seasons |

Roger Angell |

02/28/12 |

127 |

|

48. |

Robert Kennedy and His Times |

Arthur Schlesinger |

05/23/12 |

131 |

|

49. |

Confederates in the Attic |

Tony Horwitz |

09/28/12 |

133 |

|

50. |

My Life in Baseball—The True Record |

Ty Cobb with Al Stump |

12/27/12 |

137 |

|

51. |

Charlie Wilson’s War |

George Crile |

02/21/13 |

139 |

|

52. |

Season Ticket |

Roger Angell |

08/09/13 |

141 |

|

53. |

On the Road |

Jack Kerouac |

07/09/14 |

143 |

|

54. |

Rickey & Robinson |

Roger Kahn |

02/11/15 |

145 |

|

55. |

Wait Till Next Year |

Doris Kearns Goodwin |

02/11/15 |

147 |

|

56. |

You Can’t Make This Up |

Al Michaels with Jon Wertheim |

03/24/15 |

151 |

|

57. |

The Curse of Rocky Colavito |

Terry Pluto |

11/25/15 |

155 |

|

58. |

A Nice Little Place on the North Side:

Wrigley Field at One Hundred |

George Will |

12/23/15 |

157 |

|

59. |

Where Nobody Knows Your Name |

John Feinstein |

12/23/15 |

159 |

|

60. |

This Old Man |

Roger Angell |

02/05/16 |

161 |

|

61. |

Down to the Last Pitch |

Tim Wendel |

02/19/16 |

163 |

|

62. |

The Game |

Jon Pessah |

03/04/16 |

165 |

|

63. |

Alexander Hamilton |

Ron Chernow |

05/17/16 |

167 |

|

64. |

A Well-Paid Slave |

Brad Snyder |

05/25/16 |

169 |

|

65. |

Marvin Miller, Baseball Revolutionary |

Robert F. Burk |

05/26/16 |

173 |

|

66. |

Out of My League |

Dirk Hayhurst |

06/23/16 |

175 |

|

67. |

Bottom of the 33rd |

Dan Barry |

07/18/16 |

177 |

|

68. |

One Summer - America, 1927 |

Bill Bryson |

08/18/16 |

185 |

|

69. |

The Making of the President 1960 |

Theodore H. White |

10/28/16 |

189 |

|

70. |

Eisenhower in War and Peace |

Jean Edward Smith |

01/25/17 |

193 |

|

71. |

Killing the Rising Sun |

Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard |

03/17/17 |

199 |

|

72. |

Elon Musk |

Ashlee Vance |

05/17/17 |

203 |

|

73. |

Hillbilly Elegy |

J.D. Vance |

05/25/17 |

205 |

|

74. |

It Happens Every Spring |

Ira Berkow |

08/10/17 |

207 |

|

75. |

Hero of the Empire |

Candice Millard |

09/22/17 |

213 |

|

76. |

The Arm |

Jeff Passan |

09/30/17 |

215 |

|

77. |

Killing England |

Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard |

11/10/17 |

221 |

|

78. |

Summer of 68 |

Tim Wendel |

01/19/18 |

223 |

|

79. |

Gator, My Life in Pinstripes |

Ron Guidry with A. Beaton |

04/18/18 |

233 |

|

80. |

A Season in the Sun/The Rise of Mickey

Mantle |

Randy Roberts & Johnny Smith |

05/16/18 |

235 |

|

81. |

A Higher Loyalty |

James Comey |

06/29/18 |

237 |

|

82. |

The Best and the Brightest |

David Halberstam |

08/10/18 |

241 |

|

83. |

Billy Martin: Baseball’s Flawed Genius |

Bill Pennington |

09/19/18 |

245 |

|

84. |

I’m Keith Hernandez |

Keith Hernandez |

10/26/18 |

253 |

|

85. |

The Fifth Risk |

Michael Lewis |

11/21/18 |

255 |

|

86. |

The Big Fella |

Jane Leavy |

01/25/19 |

259 |

|

87. |

Killing the SS |

Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard |

02/01/19 |

261 |

|

88. |

A False Spring (Redux) |

Pat Jordan |

02/08/19 |

263 |

|

89. |

Lincoln’s Last Trial |

Dan Abrams and David Fisher |

03/15/19 |

267 |

|

90. |

RED: A Biography of Red Smith |

Ira Berkow |

05/03/19 |

269 |

|

91. |

The Catcher Was a Spy |

Nicholas Dawidoff |

05/09/19 |

277 |

|

92. |

The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Path

to Power |

Robert A. Caro |

06/20/19 |

282 |

|

93. |

The First Wave: The D-Day Warriors Who

Led the Way to Victory in World War II |

Alex Kershaw |

07/03/19 |

286 |

|

94. |

Indianapolis: The True Story of the

Worst Sea Disaster in U.S. Naval History and the Fifty-Year

Fight to Exonerate an Innocent Man |

Lynn Vincent and Sara Vladic |

08/02/19 |

288 |

|

95. |

Late Innings: A Baseball Companion |

Roger Angell |

08/13/19 |

290 |

|

96. |

No Ordinary Time - Franklin and

Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II |

Doris Kearns Goodwin |

09/13/19 |

306 |

|

97. |

Game Time, A Baseball Companion |

Roger Angell |

09/24/19 |

312 |

|

98. |

Once More Around the Park: A Baseball

Reader |

Roger Angell |

11/07/19 |

316 |

|

99. |

Master of the Senate |

Robert Caro |

02/27/20 |

334 |

SKIPPER’S TOP 10 FAVORITE BASEBALL BOOKS

|

10. |

To Every Thing A Season,

Bruce Kuklick (1991) |

|

9. |

The Boys of Summer,

Roger Kahn (1973) |

|

8. |

Men at Work, George Will

(1989) |

|

7. |

Ball Four, Jim Bouton

(1976) |

|

6. |

Summer of ’49, David

Halberstam (1989) |

|

5. |

Beyond the

Boys of Summer, Roger Kahn (2001) |

|

4. |

The Catcher was a Spy,

Nicholas Dawidoff (1994) |

|

3. |

Moneyball, Michael Lewis

(2003) |

|

2. |

October Men, Roger Kahn

(2003) |

|

1. |

Why

Time Begins on Opening Day,

Tom Boswell (1984) |

A few

comments on the above are in order:

|

** |

This list is not intended to be a paean

to Roger Kahn even though I have listed three of his books in the Top

10. I have read at least two of his other baseball books, The Head

Game and Memories of Summer, and found them to be somewhat

repetitive of his other works, and at times a bit maudlin. For my

money, however, you won’t find a baseball writer who has Kahn’s

vocabulary and his ability to turn a phrase, although Boswell can at

times give him a run for the money. |

|

|

|

|

** |

The No. 10 book on my list, To Every Thing a Season,

was a terrific historical read but not a favorite of the masses

because it dealt almost singularly with Shibe Park in Philadelphia.

You won’t find it in many bookstores, so if anybody wants to borrow my

copy, let me know. |

|

|

|

|

** |

If anybody hasn’t read The Catcher was a Spy,

you need to. It is a real page-turner, and Mo Berg was undeniably one

of the most interesting characters to don a major league uniform.

|

|

|

|

|

** |

I haven’t read Ball Four for at least twenty

years, and need to read it again to remind myself why I remember it so

fondly. If I do, I’ll let you know. |

|

|

|

|

** |

There were many great books that easily could have made

the list, and in particular, Lords of the Realm, The Babe,

The Iron Horse, Bunts, and biographies that I have read on Joe

Dimaggio, Ted Williams, Walter Johnson, John McGraw and Hank

Greenberg, the titles of which I am unable to recall. In retrospect,

I probably should elevate Lords of the Realm to the Top 10, as

it is the seminal analysis of the business of baseball, from the

reserve clause to arbitration to free agency. A long, but fascinating

study. |

BOOK

REPORT: ON THE ROAD

By Jack

Kerouac

07/08/14

Now

that I have finished reading the seminal book about the Beat Generation and

road-tripping across the USA, I can hardly believe that I waited this long

to pick up a copy and dig it. While it wasn’t one of those rare books that

I just couldn’t put down, it is definitely an intriguing story of travel and

the Beat lifestyle of a small cadre of some true and some self-styled

intellectuals. Personally, I would be uncomfortable sitting cross-legged on

a bed with any of you, staring into your eyes and “digging” you while you

blurted out some made-up nonsensical prose, following which we would both

snap our fingers. Awkward, with a capital A. But hey, I’m not judging. Now

that I have finished reading the seminal book about the Beat Generation and

road-tripping across the USA, I can hardly believe that I waited this long

to pick up a copy and dig it. While it wasn’t one of those rare books that

I just couldn’t put down, it is definitely an intriguing story of travel and

the Beat lifestyle of a small cadre of some true and some self-styled

intellectuals. Personally, I would be uncomfortable sitting cross-legged on

a bed with any of you, staring into your eyes and “digging” you while you

blurted out some made-up nonsensical prose, following which we would both

snap our fingers. Awkward, with a capital A. But hey, I’m not judging.

What I did

not know was that the “Beat” Generation had its true beginnings in the late

1940s, not the ’50s, and that most of these people were shiftless loners who

sponged off their friends and relatives to support their carefree

lifestyles. I found it somewhat surprising that there was not much talk

about the use of mind-altering substances to go along with the rampant

dialogue about all of the abundant free love that these dudes seemed to be

experiencing, until the very end of the book when they made a road trip

south of the border and got their hands on some really amazing smokes.

Timing-wise, it seems as if the Beat Generation essentially morphed into the

1960s decade of the hippies, and that the hippies took what they liked about

the beatniks (freedom, complete lack of responsibility, free-wheeling sex),

cut out the stuff they didn’t (phony intellectualism, finger-snapping), and

added in the psychedelic drugs to give their generation their own mark. Not

a terrible formula.

Bottom line

on the book: A good read. I’m guessing several of you (Stretch, Possum,

Tricko, Screech perhaps) have already read On the Road, but anyone

who hasn’t and who would like to borrow my copy, let me know and I will drop

it in the mail for your consumption. Hope you really dig it, man.

BOOK

REPORT:

SEASON

TICKET

08/09/13

I

am

about

a

fourth

of

the

way

through

a

terrific

Roger

Angell

book

that

was

recently

loaned

to

me

by

an

attorney

friend,

one

of

which

I

was

not

heretofore

aware,

entitled

Season

Ticket,

published

in

1988.

I

thought

I

had

already

read

all

of

Angell’s

baseball

anthologies,

but

thankfully,

I

was

wrong. I

am

about

a

fourth

of

the

way

through

a

terrific

Roger

Angell

book

that

was

recently

loaned

to

me

by

an

attorney

friend,

one

of

which

I

was

not

heretofore

aware,

entitled

Season

Ticket,

published

in

1988.

I

thought

I

had

already

read

all

of

Angell’s

baseball

anthologies,

but

thankfully,

I

was

wrong.

The

Penguin.

From

my

late-night

reading

last

evening

from

the

Roger

Angell

classic

“Season

Ticket,”

in

which

the

erudite

Angell

characterizes

the

declining

fielding

skills

of Ron

“The

Penguin”

Cey

during

his

1986

season

with

the

Cubs

as

being

Rodinesque

(implying,

I

think,

that

he

emulated

a

molded

statue

while

in the

field),

and in

which

he

refers

to a

headline

in the

Chicago

paper

from

that

season

which

reportedly

read:

“WASHED

UP?

CEY:

IT

AIN’T

SO!” (from FTB 10/18/13)

BOB

BRENLY—A

GAME

FOR

THE

AGES

I

previously

shared

with

all

of

you

offline

an

excerpt

from

this

book

about

the

centerfield

counterparts

in

the

1982

World

Series,

Willie

McGee

of

the

Cardinals

and

Gorman

“Walking

Strip

Mine”

Thomas

of

the

Brewers.

Here

is a

short

clip

(from

pages

14-15)

about

Bob

Brenly

that

I

absolutely

love,

particularly

the

quote

from

Roger

Craig:

In

September

1986,

during

an

unmomentous

Giants-Braves

game

out

at

Candlestick

Park,

Bob

Brenly,

playing

third

base

for

the

San

Franciscos,

made

an

error

on a

routine

ground

ball

in

the

top

of

the

fourth

inning.

Four

batters

later,

he

kicked

away

another

chance

and

then,

scrambling

after

the

ball,

threw

wildly

past

home

in

an

attempt

to

nail

a

runner

there:

two

errors

on

the

same

play.

A

few

moments

after

that,

he

managed

another

boot,

thus

becoming

only

the

fourth

player

since

the

turn

of

the

century

to

rack

up

four

errors

in

one

inning.

In

the

bottom

of

the

fifth,

Brenly

hit

a

solo

home

run.

In

the

seventh,

he

rapped

out

a

bases

loaded

single,

driving

in

two

runs

and

tying

the

game

at

6-6.

The

score

stayed

that

way

until

the

bottom

of

the

ninth,

when

our

man

came

up

to

bat

again,

with

two

out,

ran

the

count

to

3-2,

and

then

sailed

a

massive

home

run

deep

into

the

left-field

stands.

Brenly's

accountbook

for

the

day

came

to

three

hits

in

five

at-bats,

two

home

runs,

four

errors,

four

Atlanta

runs

allowed,

and

four

Giant

runs

driven

in,

including

the

game-winner.

A

neater

summary

was

delivered

by

his

manager,

Roger

Craig,

who

said,

"This

man

deserves

the

Comeback

Player

of

the

Year

Award

for

this

game

alone."

I

wasn't

at

Candlestick

that

day,

but

I

don't

care;

I

have

this

one

by

heart.

I am

taking

Season

Ticket

with

me

on

my

sojourn

next

week

to

the

Great

Northwest,

and

will

be

sure

to

highlight

some

more

delectable

tidbits

from

the

erudite

Angell

to

share

with

you

later.

BOOK

REPORT:

“Wherever

I

Wind

Up,”

by

R.A.

Dickey

05/31/13

I

finished

reading

R.A.

Dickey’s

highly

publicized

book,

co-authored

with

Wayne

Coffey,

entitled

“Wherever

I

Wind

Up.”

It

is a

very

good

read,

with

lots

of

interesting

information

about

this

journeyman

pitcher

whose

life

was

turned

around

by

the

knuckleball

and

God,

although

not

necessarily

in

that

order.

He

is

clearly

a

very

faith-filled

man,

and

the

book

is

littered

with

prayers

to

and

praise

for

the

Almighty.

(Having

said

that,

I

have

a

mental

image

of

Itchie

racing

in

his

car

at

breakneck

speed

to

the

nearest

book

store

to

pick

up

his

copy

of

the

book.

Just

saying.) I

finished

reading

R.A.

Dickey’s

highly

publicized

book,

co-authored

with

Wayne

Coffey,

entitled

“Wherever

I

Wind

Up.”

It

is a

very

good

read,

with

lots

of

interesting

information

about

this

journeyman

pitcher

whose

life

was

turned

around

by

the

knuckleball

and

God,

although

not

necessarily

in

that

order.

He

is

clearly

a

very

faith-filled

man,

and

the

book

is

littered

with

prayers

to

and

praise

for

the

Almighty.

(Having

said

that,

I

have

a

mental

image

of

Itchie

racing

in

his

car

at

breakneck

speed

to

the

nearest

book

store

to

pick

up

his

copy

of

the

book.

Just

saying.)

The

three

most

interesting

things

that

I

enjoyed

about

the

book

were:

(1)

Learning

that

Dickey

was

actually

a

flame-throwing

fastball

pitcher

as a

youth

and

in

college,

pitching

the

University

of

Tennessee

(with

the

help

of

Todd

Helton)

into

the

College

World

Series

in

Omaha

in

1995,

and

throwing

two

wins

for

the

U.S.

Olympic

bronze

medalist

team

in

Atlanta

in

1996;

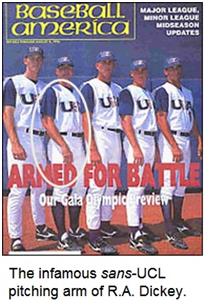

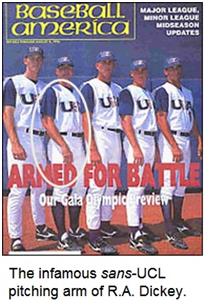

(2)

learning

that

it

was

a

photograph

of

Dickey

on

the

cover

of

Baseball

America

from

that

year

that

led

someone

in

the

Rangers

organization

to

recommend

an

MRI

of

Dickey’s

throwing

arm,

because

of

the

odd

way

that

he

was

holding

his

arm

in

the

picture—leading

to

the

discovery

of a

lack

of

an

ulnar

collateral

ligament

(UCL)

in

that

arm

and

the

retraction

of

his

$800+k

signing

bonus

by

the

Rangers;

and

(3)

discovering

that

Dickey

tried

to

swim

across

the

Missouri

River

on

June

9,

2007,

when

he

was

in

Omaha

with

the

Nashville

Sounds

for

a

game

against

the

Royals

and

staying

at

Ameristar

Casino

in

Council

Bluffs,

adjacent

to

the

river.

DUMB

JOCK

TAKES

ON

THE

MIGHTY

MO

As

to

the

river

tale,

as

the

story

goes,

Dickey

was

staring

out

of

his

room

on

one

of

the

upper

floors

of

the

casino,

admiring

the

majesty

of

the

great

Missouri

River.

He

was

reminded

of

instances

in

his

youth

when

he

swam

across

rivers

back

home

in

Tennessee,

and

decided

he

wanted

to

challenge

the

Missouri.

The

next

morning,

Dickey

walked

into

the

Missouri

River

on

the

Iowa

side,

wearing

only

a

pair

of

shorts

and

having

taped

a

pair

of

his

flip-flops

to

his

feet,

with

a

handful

of

teammates

on

the

shore

to

watch.

As

he

made

his

way

out

into

the

churning

Missouri,

he

realized

quickly

that

he

had

underestimated

its

strength,

and

struggled

to

make

progress

toward

the

Nebraska

shore.

Before

long,

he

realized

that

he

was

not

going

to

be

able

to

make

it,

and

turned

around

and

began

heading

back

toward

the

Council

Bluffs

side,

but

soon

realized

he

was

about

a

quarter

mile

south

of

the

point

of

his

embarkation.

As

he

fought

the

river,

the

muscles

in

his

arms

and

shoulders

filled

with

lactic

acid

and

became

practically

frozen,

reducing

him

to

the

dog

paddle

to

stay

alive.

As

he

was

almost

ready

to

give

up

the

ghost,

he

neared

the

Iowa

shore

and

the

hand

of a

teammate—Grant

Balfour—reached

out

from

the

heavens

and

helped

pull

him

out

of

the

water.

He

survived

the

swim,

and,

as

he

tells

it

in

his

book,

his

life

was

turned

around

from

that

moment

on

because

he

realized

that

he

was

not

the

one

in

control,

and

he

gave

his

life

over

to

his

Maker.

He

went

from

having

a

2-5

pitching

record

at

that

point

and

a mastodonic

ERA

to

winning

the

AAA

Pitcher

of

the

Year

Award,

and

the

rest

is

history.

When

I

saw

that

Grant

Balfour

was

the

teammate

who

pulled

Dickey

out,

I

looked

back

at

my

own

records

and

discovered

that

it

was

the

evening

prior

to

this

heroic

rescue

that

Balfour

had

uncorked

a

wild

pitch

from

the

Nashville

bullpen

at

Rosenblatt

and

struck

a

fan

named

Schrader

in

the

eye,

leading

to a

lawsuit

being

filed

by

him

against

the

Omaha

Royals

and

my

subsequent

taking

of

the

deposition

of

Mr.

Balfour

at

spring

training

in

Florida

in

2009.

A

pretty

eventful

two

days

for

the

Aussie

Balfour,

who

is

now

the

closer

for

the

Oakland

Athletics. When

I

saw

that

Grant

Balfour

was

the

teammate

who

pulled

Dickey

out,

I

looked

back

at

my

own

records

and

discovered

that

it

was

the

evening

prior

to

this

heroic

rescue

that

Balfour

had

uncorked

a

wild

pitch

from

the

Nashville

bullpen

at

Rosenblatt

and

struck

a

fan

named

Schrader

in

the

eye,

leading

to a

lawsuit

being

filed

by

him

against

the

Omaha

Royals

and

my

subsequent

taking

of

the

deposition

of

Mr.

Balfour

at

spring

training

in

Florida

in

2009.

A

pretty

eventful

two

days

for

the

Aussie

Balfour,

who

is

now

the

closer

for

the

Oakland

Athletics.

Book

Report:

Charlie

Wilson’s

War

02/21/13

Many

or most of

you have

probably

seen the

movie

Charlie

Wilson’s

War,

starring

Tom Hanks

and

Seymour

Hoffman,

but if you

haven’t

read the

book by

George

Crile, you

are

selling

yourself

short. I

just

finished

reading

this

marvelous

tale of

intrigue,

politics

and sex,

and it is

indeed a

page-turner.

Until

reading

this book,

I had

absolutely

no idea of

the amount

of money

that was

committed

by the

United

States to

fund and

arm the

Afghan

rebels in

their

thirteen-year

occupation

by and war

with the

Soviet Red

Army. And

from

reading

the book,

I have a

much

better

understanding

of why so

many

people

from that

region of

the world

hate the

United

States of

America—they

believe

that we

absolutely

turned our

backs on

them after

they

fought

this

surrogate

war

against

Communism

for us. Many

or most of

you have

probably

seen the

movie

Charlie

Wilson’s

War,

starring

Tom Hanks

and

Seymour

Hoffman,

but if you

haven’t

read the

book by

George

Crile, you

are

selling

yourself

short. I

just

finished

reading

this

marvelous

tale of

intrigue,

politics

and sex,

and it is

indeed a

page-turner.

Until

reading

this book,

I had

absolutely

no idea of

the amount

of money

that was

committed

by the

United

States to

fund and

arm the

Afghan

rebels in

their

thirteen-year

occupation

by and war

with the

Soviet Red

Army. And

from

reading

the book,

I have a

much

better

understanding

of why so

many

people

from that

region of

the world

hate the

United

States of

America—they

believe

that we

absolutely

turned our

backs on

them after

they

fought

this

surrogate

war

against

Communism

for us.

I recently

ran into a

couple of

lawyers

from East

Texas when

I was at

the

national

ABOTA

convention

in St.

Pete, and

they were

represented

by Charlie

Wilson for

many years

and

confirmed

the image

of him in

the book

as a

playboy/party-hound-turned-American-hero.

This book

is a great

read. I

heartily

recommend

it.

BOOK

REPORT:

FIVE

SEASONS

02/28/12

It

has been a

while

since I

have done

a book

report, so

let me

take this

opportunity

to tout a

sublime

baseball

read that

I just

finished,

Five

Seasons

by Roger

Angell.

First

published

in 1977,

Five

Seasons

is a

collection

of

Angell’s

writings

covering

parts of

the

baseball

seasons of

1972

through

1976. It

has been a

while

since I

have done

a book

report, so

let me

take this

opportunity

to tout a

sublime

baseball

read that

I just

finished,

Five

Seasons

by Roger

Angell.

First

published

in 1977,

Five

Seasons

is a

collection

of

Angell’s

writings

covering

parts of

the

baseball

seasons of

1972

through

1976.

If I had

the

ability to

write like

Roger

Angell, I

could

articulate

much more

pellucidly

why it is

that

Five

Seasons

is such a

great

read. In

spite of

my

limitations,

I will

try.

Angell has

a writing

style

which is

so

descriptive

and so

nuanced

that at

times you

feel as if

you are

actually

present

with him

when he is

making his

observations

about the

game of

baseball

and its

many

facets and

colorful

personalities.

I feel

like he is

showing me

a few

glimpses

of life

that the

general

population

never has

a chance

to see,

that I am

one of the

privileged

few who

get to

know his

thinking

on

baseball

matters.

I think my

favorite

part of

the book

was

Angell’s

recounting

of the

1975 World

Series

between

the Big

Red

Machine of

Cincinnati

and the

Boston Red

Sox, quite

possibly

the best

World

Series of

all time.

Angell

reminds us

that the

Red Sox

were ahead

of the

Reds in

every

single one

of the

seven

games,

despite a

clear

disparity

in talent,

but that

the Big

Red

Machine

was able

to come

back to

win four

of those

games,

including

the

deciding

Game 7 at

Fenway. I

love the

following

excerpts

from

Angell

about this

Series:

Bernie

Carbo,

pinch-hitting,

looked

wholly

overmatched

against

Eastwick,

flailing

at one

inside

fastball like

someone

fighting

off a wasp

with a

croquet

mallet.

One more

fastball

arrived,

high and

over the

middle of

the plate,

and Carbo

smashed it

in a

gigantic,

flattened

parabola

into the

center-field

bleachers,

tying the

game.

~~

And so the

swing of

things was

won back

again.

Carlton

Fisk,

leading

off the

bottom of

the

twelfth

against

Pat Darcy,

the eighth

Reds

pitcher of

the

night—it

was well

into

morning

now, in

fact—socked

the second

pitch up

and out,

farther

and father

into the

darkness

above the

lights,

and when

it came

down at

last,

reilluminated,

it struck

the

topmost,

innermost

edge of

the screen

inside the

yellow

left-field

foul pole

and

glanced

sharply

down and

bounced on

the grass;

a fair

ball, fair

all the

way. I was

watching

the ball,

of course,

so I

missed

what

everyone

on

television

saw—Fisk

waving

wildly,

weaving

and

writhing

and

gyrating

along the

first-base

line, as

he wished

the ball

fair,

forced it

fair with

his entire

body. He

circled

the bases

in

triumph,

in sudden

company

with

several

hundred

fans, and

jumped on

home plate

with both

feet, and

John Kiley,

the Fenway

Park

organist,

played

Handel’s

“Hallelujah

Chorus,”

fortissimo,

and then

followed

with other

appropriately

exuberant

classical

selections,

and for

the second

time that

evening I

suddenly

remembered

all my old

absent and

distant

Sox-afflicted

friends

(and all

the other

Red Sox

fans, all

over New

England),

and I

thought of

them—in

Brookline,

Mass., and

Brooklin,

Maine; in

Beverly

Farms and

Mashpee

and

Presque

Isle and

North

Conway and

Damariscotta;

in Pomfret,

Connecticut,

and

Pomfret,

Vermont;

in Wayland

and

Providence

and Revere

and

Nashua,

and in

both the

Concords

and all

five

Manchesters;

and in

Raymond,

New

Hampshire

(where

Carlton

Fisk

lives),

and

Bellows

Falls,

Vermont

(where

Carlton

Fisk was born),

and I saw

all of

them

dancing

and

shouting

and

kissing

and

leaping

about like

the fans

at

Fenway—jumping

up and

down in

their

bedrooms

and

kitchens

and living

rooms, and

in bars

and

trailers,

and even

in some

boats here

and there,

I suppose,

and on

back-country

roads (a

lone

driver

getting

the news

over the

radio and

blowing

his horn

over and

over, and

finally

pulling up

and

getting

out and

leaping up

and down

on the

cold

macadam,

yelling

into the

night),

and all of

them, for

once at

least,

utterly

joyful and

believing

in that

joy—alight

with it.

~~

The

seventh

game,

which

settled

the

championship

in the

very last

inning and

was

watched by

a

television

audience

of

seventy-five

million

people,

probably

would have

been a

famous

thriller

in some

other

Series,

but in

1975 it

was

outclassed.

It

was a good

play that

opened on

the night

after the

opening

night of

King Lear.

~~

Rose led

off with a

single in

the

sixth.

(He got on

base

eleven

times in

his last

fifteen

appearances

in the

Series.)

With one

out, Bench

hit a sure

double-play

ball to

Burleson,

but Rose,

barreling

down

toward

second,

slid high

and hard

into Doyle

just as he

was firing

on to

first, and

the ball

went

wildly

into the

Boston

dugout.

Lee, now

facing

Perez,

essayed a

looping,

quarter-speed,

spinning

curve, and

Perez,

timing his

full swing

exactly,

hit the

ball over

the wall

and over

the screen

and

perhaps

over the

Massachusetts

Turnpike.

The Reds

then tied

the game

in the

seventh

(when Lee

was

permitted

to start

his winter

vacation),

with Rose

driving in

the run.

The

Cincinnati

bullpen

had

matters in

their

charge by

now, and

almost the

only

sounds

still to

be heard

were the

continuous

cries and

clappings

and shouts

of hope

from the

Reds’

dugout.

Fenway

Park was

like a

waiting

accident

ward early

on a

Saturday

night.

Five

Seasons

is a

quintessential

baseball

read and a

delightful

baseball

companion.

And if you

spend the

evening at

the

ballpark

with

Roger, you

will not

wake up

with a

ringing

Jägerbomb

hangover

such as

you might

experience

after

hanging

out with

certain

other

baseball

companions.

Just

saying.

BOOK

REVIEW:

Counselor:

A

Life

at

the

Edge

of

History

(09/26/11)

Finally,

let

me

commend

to

you

heartily

a

wonderful

book

written

by

Lincoln

native

Ted

Sorensen,

entitled

Counselor:

A

Life

at

the

Edge

of

History.

This

marvelous

book

details

some

of

the

high

and

low

points

of

Sorensen’s

career

in

politics

and

law,

including

being

“in

the

loop”

for

such

historic

events

as

the

Bay

of

Pigs,

the

Cuban

missile

crisis,

the

launching

of

the

space

program

to

beat

the Ruskies

to

the

moon,

and

the

establishment

of

the

Peace

Corps. Finally,

let

me

commend

to

you

heartily

a

wonderful

book

written

by

Lincoln

native

Ted

Sorensen,

entitled

Counselor:

A

Life

at

the

Edge

of

History.

This

marvelous

book

details

some

of

the

high

and

low

points

of

Sorensen’s

career

in

politics

and

law,

including

being

“in

the

loop”

for

such

historic

events

as

the

Bay

of

Pigs,

the

Cuban

missile

crisis,

the

launching

of

the

space

program

to

beat

the Ruskies

to

the

moon,

and

the

establishment

of

the

Peace

Corps.

I

did

not

know

that Sorensen’s

father

was

once

the

Attorney

General

for

the

state

of

Nebraska,

and

a

reported

shoo-in

for

a

federal

judgeship

in

Lincoln,

until

partisan

politics

intervened.

I

also

did

not

know

that

his

mother

was

of

Jewish

lineage,

and

a

nut

case.

I

probably

knew

at

one

time

but

had

forgotten

that

Jimmy

Carter

nominated

Ted

Sorensen

to

lead

the

CIA,

until

he

found

out

that

his vetters

had

missed

the

fact

that

Sorensen

was

a

conscientious

objector,

ultimately

leading

to

Sorensen’s

painful

withdrawal

from

the

Senate

confirmation

process.

It

was

quite

clear

from

the

book

that

Sorensen

has

little

respect

for

the

former

peanut

farmer

from

Georgia,

or

for

Senator

Joe

Biden,

who

turned

his

back

on

Sorensen

during

the

CIA

confirmation

fiasco.

My

favorite

quote

from

the

book

was

about

the

CIA

after

agency

heads

persuaded

JFK

to

approve

of

the

Bay

of

Pigs

mission.

The

CIA:

“Often

wrong,

but

never

in

doubt.”

Sounds

like

somebody

in

this

league

that

we

all

know

very

well.

My

second

favorite

quote

in

the

book

is

from

Harry

Truman,

whom

Sorensen

cited

for

the

famous

“If

you

want

a

friend

in

Washington,

buy

a

dog”

line

after

his

support

to

be

the

director

of

the

CIA

collapsed

like

a

house

of

cards.

In

any

event,

you

will

do

yourself

a

favor

if

you

choose

to

read

this

great

book.

If

you

want

to

borrow

my

copy,

let

me

know.

THE

YANKEE

YEARS

(04/08/11)

I’m

about

two-thirds

of

the

way

through

an

excellent

book

called

The

Yankee

Years,

written

by

Joe

Torre

(sort

of)

and

Tom

Verducci

(mostly).

To

lead

with

a

quote

from

the

Daily

News,

it

is

“one

of

the

best

books

about

baseball

ever

written.”

I

agree. I’m

about

two-thirds

of

the

way

through

an

excellent

book

called

The

Yankee

Years,

written

by

Joe

Torre

(sort

of)

and

Tom

Verducci

(mostly).

To

lead

with

a

quote

from

the

Daily

News,

it

is

“one

of

the

best

books

about

baseball

ever

written.”

I

agree.

Verducci

is

an

excellent

writer,

and

Torre

is

full

of

great

insight

about

his

Yankee

teams

from

1996

to

2007.

It

is

absolutely

required

reading

for

a

Yankee

fan,

so

Screech

and

Mouse,

get

busy.

However,

if

you

are

merely

a

baseball

fan,

and

all

of

you

are

rabid

ones

at

that,

you

should

do

yourselves

a

favor

and

read

this

book.

Just

to

whet

your

appetite,

one

of

the

fascinating

things

that

is

pointed

out

by

the

book

is

how

important

healthy

starting

pitching

is

to a

team’s

success.

During

Torre’s

years

at

the

helm

of

the

Yankee

Clipper,

there

was

one

year

when

only

two

of

his

starters

made

at

least

25

starts,

and

that

was

2005.

In

1997,

2001,

2002,

2004

and

2007,

three

of

his

starting

pitchers

made

at

least

25

starts.

In

1996,

1998,

2000,

2003

and

2006,

four

of

his

starters

made

at

least

25

starts.

In

1999,

five

of

his

starters

made

at

least

25

starts.

Torre’s

four

World

Championships

came

in

1996,

1998,

1999

and

2000,

all

in

years

in

which

either

four

or

five

of

his

team’s

starters

made

at

least

25

starts.

Obviously,

not

just

a

coincidence.

There

is

much

more

great

stuff

to

share

with

you

from

this

book.

If I

remember

to

do

so,

I

will

include

a

few

more

tidbits

in

future

Bullpens.

BOOK RECOMMENDATION:

Last Lion: The Fall and Rise of Ted Kennedy

(02/09/11)

Before I close out this short issue of From the Bullpen, let me just put in a short plug for a terrific book that I just finished reading, Last Lion: The Fall and Rise of Ted Kennedy, authored by a team of reporters at The Boston Globe, and edited by Peter Canellos. I can sense that seven or eight of the rock-ribbed Republicans in this group are already turning their noses up at the idea of reading anything about Ted Kennedy –– you know who you are –– and so I’m going to suggest to those of that ilk that it is especially important that each of you read this book, if you can possibly do it with an open mind. Haa! Maybe when pigs can beam through space. But if you can, I think that you will come away from reading this book with an entirely different perception of Ted Kennedy than you have right now. For at least the last ten or fifteen years of his life, Kennedy actually did a whole heck of a lot of good, whether you agree with his political philosophy or not, and my whole perception of him has changed after reading this extremely well-written book. Before I close out this short issue of From the Bullpen, let me just put in a short plug for a terrific book that I just finished reading, Last Lion: The Fall and Rise of Ted Kennedy, authored by a team of reporters at The Boston Globe, and edited by Peter Canellos. I can sense that seven or eight of the rock-ribbed Republicans in this group are already turning their noses up at the idea of reading anything about Ted Kennedy –– you know who you are –– and so I’m going to suggest to those of that ilk that it is especially important that each of you read this book, if you can possibly do it with an open mind. Haa! Maybe when pigs can beam through space. But if you can, I think that you will come away from reading this book with an entirely different perception of Ted Kennedy than you have right now. For at least the last ten or fifteen years of his life, Kennedy actually did a whole heck of a lot of good, whether you agree with his political philosophy or not, and my whole perception of him has changed after reading this extremely well-written book.

For the proletariat members of the league, Last Lion will be a rallying cry for justice and equality for all.

So, bottom line, whatever your party affiliation, whether you are on the leftist fringe, a committed right-winger, or a sensible centrist like myself, this book is a good and worthy read.

|

BOOK REPORT: BOOK REPORT:

9 Innings: The anatomy of a baseball game

Finally, although I don’t have the time to do a full book review for you, I want to commend to you an excellent baseball book that I finished reading last fall, entitled 9 Innings: The anatomy of a baseball game, authored by the seasoned baseball scribe, Daniel Okrent. The entire book is centered around a single baseball game between the Milwaukee Brewers and the Baltimore Orioles which took place in June 1982. There are lots of great excerpts from this book, some of which I may share with you later when time allows, but my favorite story is about the Orioles' crusty manager, the Earl of Baltimore, Earl Weaver, as follows:

Weaver drank a lot, and managed to disarm his critics by acknowledging his frailty and by managing to issue the perfect response in the most embarrassing situations. At his most recent arrest, which resulted in the suspension of his driver’s license, the arresting officer had asked if Weaver had any physical disabilities. “Only Jim Palmer,” he said, referring to the cranky nonpareil of the Baltimore pitching staff.

Great stuff. Do yourself a favor and read this great book. |

BOOK

REVIEW:

Chief

Bender’s

Burden

(03/04/10)

Speaking

of

the

book

Chief

Bender’s

Burden,

I

finished

it

up

on

my

flight

home

from

California,

and

so

let

me

give

you

this

short

review.

Written

by a

relatively

unknown

Minnesota

author

by

the

name

of

Tom

Swift

in

2008,

this

book,

published

by

the

University

of

Nebraska

Press

in

Lincoln,

is

based

on

the

premise

that

Bender

was

the

subject

of

much

anti-American

Indian

sentiment

and

prejudice,

and

that

he

had

to

learn

to

survive

in

the

white

man’s

world

in

order

to

become

a

star

baseball

pitcher.

The

subtitle

is

“The

Silent

Struggle

of a

Baseball

Star.” Speaking

of

the

book

Chief

Bender’s

Burden,

I

finished

it

up

on

my

flight

home

from

California,

and

so

let

me

give

you

this

short

review.

Written

by a

relatively

unknown

Minnesota

author

by

the

name

of

Tom

Swift

in

2008,

this

book,

published

by

the

University

of

Nebraska

Press

in

Lincoln,

is

based

on

the

premise

that

Bender

was

the

subject

of

much

anti-American

Indian

sentiment

and

prejudice,

and

that

he

had

to

learn

to

survive

in

the

white

man’s

world

in

order

to

become

a

star

baseball

pitcher.

The

subtitle

is

“The

Silent

Struggle

of a

Baseball

Star.”

My

overall

assessment

of

this

book

is

that

it

is

an

earnest

attempt

by a

neophyte

author

to

make

the

case

that

Charles

“Chief”

Bender

was

worthy

of

the

baseball

Hall

of

Fame

because

of

his

struggles

against

prejudice,

as

much

as

for

his

statistics,

which

seem

marginal

compared

to

qualifications

of

modern

starting

pitchers

who

are

under

consideration

for

the

Hall

of

Fame.

Swift’s

book

begins

with

Chief

Bender’s

preparations

to

pitch

the

opening

game

of

the

1914

World

Series

between

the

powerful

Philadelphia

Athletics

of

Connie

Mack

and

the

“Miracle”

Boston

Braves,

who

were

in

last

place

in

the

National

League

in

early

July

1914,

fifteen

games

behind

the

powerful

New

York

Giants

of

Mugsy

McGraw.

On

July

15

of

that

season,

the

Braves

were

in

last

place

with

a

record

of

33-43,

while

McGraw’s

Giants

appeared

to

be

cruising

to a

fourth

straight

NL

pennant.

However,

the

Braves

caught

fire

in

the

second

half

of

the

season,

and

ended

up

winning

the

National

League

pennant

over

the

Giants

by a

whopping

10-1/2

games.

They

then

boldly

thumped

the

powerful

Mack

Men

in

the

1914

Series,

beating

the

theretofore

almost

invincible

Chief

Bender

in

the

first

game

of

the

Series

and

rolling

on

to

an

unthinkable

4-0

Series

sweep.

While

Bender’s

Burden

provides

some

great

information

about

the

powerful

Athletics

in

the

first

two

decades

of

the

last

century

and

the

general

state

of

things

in

the

dead

ball

era,

Swift’s

prose

often

jumps

around

from

year

to

year

in

such

a

way

as

to

be

distracting,

and

it

is

often

hard

to

follow

which

season

and

which

team

he

is

talking

about.

Unlike

most

of

the

books

I

have

reviewed

in

From

the

Bullpen,

I

cannot

heartily

recommend

this

one

to

you.

Rather,

allow

me

just

to

share

with

you

a

few

of

the

interesting

revelations:

|

* |

Charles Albert Bender was born either on May 3 or May 5, 1883 or 1884 in Crow Wing County in Northern Minnesota, about 20 miles east of Brainerd, which is often called his birthplace. His father, Albertus Bliss Bender, was one of the early white settlers in Minnesota, a homesteader-farmer of German-American descent. His mother, Mary Razor Bender, was believed to have been a member of the Mississippi band of the Ojibwe tribe, and her Indian name was Pay Shaw De O Quay.

|

|

* |

Shortly after his birth, the Bender family moved to the White Earth reservation in Minnesota, and Bender spent many of his young years on the reservation. Eventually, after receiving a kick in the pants from his father (the details of all of this seem quite suspect), Bender ran away from the reservation and found his way to Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where he attended the famous Carlisle Indian Industrial School of Jim Thorpe fame. Although he pitched for the Carlisle High School team, his high school athletic prowess would have led no one to believe that he would go on to become a Hall of Fame pitcher for the Philadelphia Athletics.

|

|

* |

After high school, Bender was recruited to play for the Harrisburg (PA) Athletic Club, and his success with that organization in the early years of the century led to his signing by Connie Mack in 1902, reportedly to a contract which would pay him $300 a month. He made his major league debut on April 20, 1903 in relief of Rube Waddell, and made his first start on April 27, 1903, twirling the Athletics to a 6-0 win over the Highlanders. At 19 years of age in 1903, Bender had one of the best age-19 seasons in the history of the major leagues. He won 17 games, completed 29, and shut out 2 opponents. He ended up with a 3.07 ERA in 270 innings of work, striking out 127 batters and walking only 65. In spite of his pitching prowess, the Athletics finished second to the powerful Boston Americans by 14-1/2 games in the inaugural major league season of the American League, and the Americans went on to beat the Pittsburgh Pirates in the first World Series.

|

|

* |

Bender began earning his reputation as a big-game pitcher in the 1905 World Series, when he threw a 3-0 shutout in Game Two of the ’05 Series against Christy Mathewson’s Giants, besting Iron Man Joe McGinnity. In Game 5, he valiantly pitched a five-hitter against the great Christy Mathewson, but Mathewson threw his third shutout of the Series and the Giants beat the Athletics by the tune of 2-0.

|

|

* |

Bender would go on to be the starting pitcher for the Athletics in Game One of the 1910, 1911, 1913 and 1914 World Series. He ended up with a 6-4 World Series mark, a 2.44 World Series ERA, and the utmost respect of his peers and of Connie Mack for his clutch pitching.

|

|

* |

Swift suggests, with very little proof, that an Itchie-like battle with the bottle was the reason that Bender got battered in the Opening Game of the 1914 World Series by the clearly inferior Boston Braves, and that this same native taste for illicit spirits was the reason that Connie Mack put him on waivers at the conclusion of the 1914 season. Seems more likely to me that it was Bender’s signing with the upstart Federal League that led to his waiver by Mack.

|

|

* |

Bender completed his major league career with 212 wins, 127 losses, a 2.46 ERA, pitching 3017 innings, giving up 2645 hits, striking out 1711 batters and walking 712. His career WHIP of 1.113 is phenomenal. He was elected to the Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1953, and died on May 22, 1954 in Philadelphia.

|

|

* |

It is clear from Swift’s book that Bender was an upright, intelligent, articulate and honorable individual who was well-liked by all who crossed his path. It is also clear that he did in fact overcome great prejudice to become one of the great major league pitchers of all time, and likely the greatest American Indian pitcher.

|

So

now

you

know

the

story

of

Chief

Bender’s

Burden.

BOOK

REPORT:

The

Snowball:

Warren

Buffett

and

the

Business

of

Life

(01/29/10)

For

those

of

you

who

have

not

yet

read

it,

I

highly

recommend

the

seminal

work

on

Warren Buffett,

titled

above,

written

by

Alice

Schroeder,

who

was

granted

virtually

unlimited

access

to

Buffett

and

his

cadre

of

business

associates,

friends,

and

family

members,

including

the

Cardinal

of

Curmudgeons,

Charlie

Munger.

In a

word,

the

book

is

fascinating.

At

800

pages

in

length,

it

is a

bit

intimidating

to

start,

but

it

is a

page-turner

that

I

polished

off

in

about

three

weeks.

The

Oracle

of

Omaha

is a

incredibly

brilliant

man,

but

as

Ms.

Schroeder

demonstrates

in

abundance,

he

is

an

extraordinarily

complex

man

with

a

highly

underdeveloped

ability

to

deal

with

his

own

emotions.

Perhaps

because

of

his

refusal

to

deal

with

his

own

father’s

death,

or

because

of

the

emotional

battering

that

he

and

his

siblings

took

from

their

crackpot

mother,

Buffett

simply

cannot

deal

with

the

illnesses

and

deaths

of

his

family

members

and

close

friends.

Remarkably,

he

was

not

even

able

to

attend

the

memorial

service

of

his

late

wife,

Susie,

although

the

celebrated

Bono

was

there,

no

doubt

trying

to

cement

a

large

donation

to

one

of

his

many

charitable

causes.

There

are

so

many

great

stories

from

“Snowball”

that

I

could

share

with

you

to

whet

your

appetite

for

this

book,

but

I

don’t

want

to

spoil

it

for

you.

Let’s

just

say

that

if

you’re

from

Nebraska

and

you

like

to

read,

you

won’t

want

to

miss

out

on

this

great

book.

BOOK

REVIEW:

CRACKING

THE

SHOW,

by

Tom

Boswell

(12/23/09)

THE

RUINATION

OF

FERNANDO

I am

almost

done

reading

another

excellent

book

from

Tom

Boswell,

entitled

“Cracking

the

Show,”

which

is

basically

another

collection

of

his

newspaper

articles.

Good

God,

I

love

this

man.

I

could

read

his

stuff

every

single

day,

and

for

the

most

part,

I

do. I am

almost

done

reading

another

excellent

book

from

Tom

Boswell,

entitled

“Cracking

the

Show,”

which

is

basically

another

collection

of

his

newspaper

articles.

Good

God,

I

love

this

man.

I

could

read

his

stuff

every

single

day,

and

for

the

most

part,

I

do.

Anyway,

Boswell

has

a

chapter

in

the

book

called

“Won’t

Fade

Away,”

which

includes

an

article

about

Fernando

Valenzuela

dated

May

20,

1989,

captioned

“Valenzuela

Syndrome.”

The

subject

of

the

article

is

the

overuse

of

rookie

sensation

Fernando

Valenzuela

by

the

Dodgers

between

1982

and

1987,

and

the

impact

it

had

on

his

career.

At

the

time

he

wrote

the

article,

Fernando

was

still

pitching

for

the

Dodgers,

but

was

coming

off

of a

5-8

season

in

1988

and

a

14-14

campaign

in

1987,

and

was

showing

all

the

signs

of

being

washed

up.

Although

he

finished

the

1989

season

with

a

record

of

10-13,

at

the

time

Boswell

wrote

his

article,

Fernando

was

winless,

and

as

said

by

Boswell,

“reduced

to

junk

balling.”

As

Bowell

put

it,

“the

Los

Angeles

Dodgers

have

all

but

ruined

him.

They

didn’t

mean

it.

They

just

didn’t

know

then

what

everybody’s

learning

now:

The

faster

you

rise,

the

faster

you

fall.”

Boswell

later

asks

the

question,

“How

slow

is

Fernando?

When

utility

man

Mickey

Hatcher

pitched

in

the

Dodgers’

blowout

recently,

the

radar

gun

clocked

him

at

82

mph—the

same

speed

as

Valenzuela,

who

sometimes

can’t

get

to

80.

This

is

the

same

man

whose

fastball

once

set

up

1,048

strikeouts

in

seven

years.”

After

reading

this

great

article,

I

looked

up

Fernando’s

stats.

Sure

enough,

he

was

abused

badly

by

the

Dodgers.

In

his

rookie

campaign

in

1981,

Fernando

pitched

192.1

innings,

finishing

with

a

13-7

record,

with

11

complete

games

and

8

shutouts.

The

following

season,

1982,

they

pitched

him

285

innings,

including

18

complete

games.

In

1983,

it

was

257.0

innings

and

9

complete

games.

In

1984,

it

was

261

innings

and

12

complete

games.

In

1985,

272

innings

and

14

complete

games.

And

in

1986,

269

innings

and

20

complete

games.

After

Boswell’s

article,

Fernando

continued

to

pitch,

bouncing

around

from

the

Dodgers

to

the

Angels

to

the

Orioles

to

the

Phillies

to

the

Padres

to

the

Cardinals,

notching

a

45-63

won-loss